Post Kraft/Cadbury M&A activity in the UK

- 8th April 2014

- Written by LSBF Staff

- Opinion & Features

In this article, Lecturer Paul Bisping discusses and analyses post-Kraft/Cadbury activity in the UK

7 September 2009 is a date enshrined in the UK mergers and acquisitions calendar. On that Monday morning over 4 years ago the takeover of Cadbury by Kraft foods set in motion a litany of changes to takeover rules in the UK. By January 2010 and after several higher bid announcements, Cadbury’s shareholders followed Chairman, Roger Carr’s advice and accepted Kraft’s final offer.

Less than a few months after guaranteeing the continued operation of the Somerdale Plant in Bristol that Cadbury had announced in 2007 would be closed, Kraft changed their mind and shut it down, axing 500 UK jobs and provoking questions about the public relations tactics of Kraft’s CEO and Chairman, Irene Rosenfield. MPs were up in arms at the change in tack and were livid that Rosenfield had shown little respect for national politics by refusing to turn up to address a hostile parliamentary committee investigating the deal.

The Takeover Panel who has oversight for all UK bid activity decided, in light of the discussions that came out of this story, to significantly tighten the rules on ‘virtual bids’ in the UK, as well as the mechanics of announcements during takeover bids. On 19 September 2011, following the takeover of the UK’s largest confectionary company, a contentious rule, known as the ‘put up or shut up’ (PUSU) deadline was introduced in a revision of the existing ‘Blue Book’ code (the Blue Book is the 300-page bible that outlines the acceptable behaviour and rules during a takeover bid). The PUSU condition mandated a 28 day (4 week) maximum period by which a potential bidder must come public with their intention to make or not make a firm bid for the target company, and must also reveal their identity. The Panel also tightened rules to improve the disclosure of information and to provide greater recognition of the interests of offeree company employees.

The reforms came after a lengthy consultation paper, PCP 2010/2, was introduced by the Takeover Panel. Since its inception in the late 1960s as a self-regulatory City body, the remit of this panel has been to protect shareholders of the target company in takeover transactions.

Why the need for protection? Shareholders can be short-changed by opportunistic attempts to realise value from undervalued and failing companies vulnerable to takeover attempts. However, critics have argued that the balance of power shifted too far the other way, allowing the boards of target companies to determine the outcome of a proposed offer and increase their power to thwart potential takeovers.

One of the most significant outcomes of the PUSU deadline imposition has been that confidentiality and secrecy are deemed even more important than previously, as any leak in a takeover bid will lead to a PUSU time limit and possible withdrawal of the bidder. Interestingly, only the target company’s board, and not the offeror, can seek an extension to a PUSU deadline and so the target company has greater control than under the old system. According to Herbert Smith in a report on their website, in 12 out of 19 extensions granted, the first extension was for 28 days. Subsequent extensions tend to be sought and awarded in multiples of 7 days. Target companies, although seemingly having the sole authority to ask for an extension, must consider the best interests of their shareholders, leaving them with little choice but to ask for an extension if the bidder does not make the 28 day deadline.

The Code Committee, the division responsible for the ‘Blue Book’ takeover code, considers that the rule changes have worked well and, in a consultation document in November 2012, wrote: “There is no evidence of offeree companies having been put under siege for protracted periods. In addition, in the year ended 18 September 2012, there was a significant reduction in the proportion of offer periods which commenced with the announcement of a “possible offer” following rumour and speculation and/or an untoward movement in the offeree company’s share price. Subsequent to the changes there was a significant increase in the proportion of offer periods that commenced with the announcement of a firm offer”.

As Tony Pullinger, the Deputy Director General at The Takeover Panel stated in an interview with the Daily Telegraph in 2012 , the goal for The Panel had been realised, as the period between the approach and offer announcement had fewer forced announcements due to market movements and, most importantly, began with a substantially higher proportion of definite, rather than possible, bid offers. The major concern of the financial markets and The Takeover Panel – that target companies could be weakened as a result of virtual bids, management could be distracted by the persistent presence of a stalker in the background and the probability of a hostile takeover would increase – had been surmounted.

The UK finance industry has been worried about the implications of the new PUSU rules. In particular they worry about a reduction in the number and the value of takeover transactions in the UK. Are these concerns valid?

A cursory statistical assessment of the impact of the PUSU introduction on transaction activity could be helpful in answering these concerns. If there was a noticeable deterioration in the number and value of M&A transactions within the UK – and between the UK and European, US and ROW transaction activity – then perhaps the blame could be partly attributed to the rule changes on 19 September 2011 by the Code Committee of The Panel?

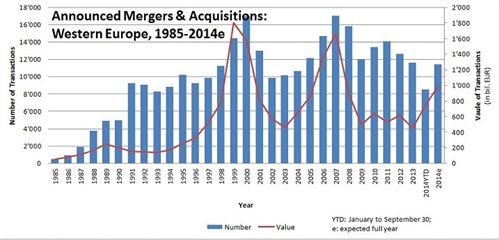

*Click on the graphs to view in full screen.

Source: https://imaa-institute.org/mergers-and-acquisitions-statistics/#MergersAcquisitions_Worldwide

There is no debating the fact illustrated in the above graph – that the value of transactions almost halved from 2010 to 2013 in the UK. The number of transactions seemingly held up well though. One assumption that could be made from this basic data is that although having little impact on overall activity levels, the significant reduction in the value of deals could result from a reduction in transnational deals in the UK.

Experts had argued strenuously that the complexities of cross-border deals made the 28 day calendar an exceptionally tough hurdle to negotiate in the post-Cadbury world. Indeed the comparison of UK deals activity with the rest of Europe point to that very argument, with the number of deals in the UK comparing favourably. Larger deals tend to be the cross-border variety.

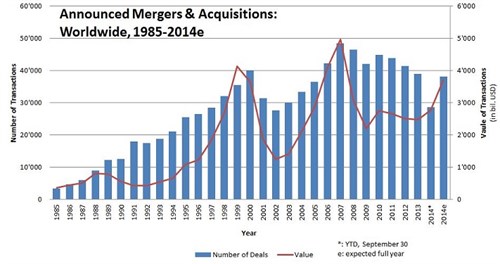

Source: https://imaa-institute.org/mergers-and-acquisitions-statistics/#MergersAcquisitions_Worldwide

This shows a very stable past 3 years in the number and value of M&A transactions worldwide.

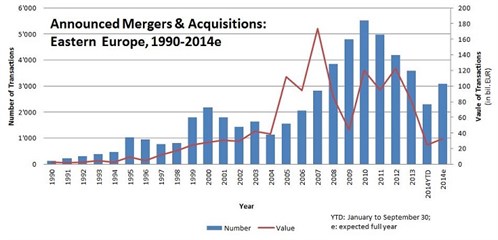

Source: https://imaa-institute.org/mergers-and-acquisitions-statistics/#MergersAcquisitions_Worldwide

Europe on the other hand has experienced a decline in the value of deals since 2010, although not as significantly as the UK. The number of transactions during the Cypriot mini crisis probably affected sentiment and was a more significant fall than in the UK post the introduction of the PUSU rule.

Surprisingly, however, a quick glance at the most recent statistics provided by the Office for National Statistics suggests that there is little evidence of a decline in either the value, or indeed, the number of overseas bidders for UK companies.

The 2 Q 2013 indicates the strongest period for many years, but as with most small data pools, it has been skewed by a single factor: the Glencore deal for Xtrata in the mining sector. Excluding this one deal, the value of acquisitions in the UK by foreign companies has indeed fallen, from the £10-15bn quarterly level in 2005-2010 (except for the financial crisis Q3 2008 to Q3 2009) to the £2-5bn range post-2010. How much of that is due to the new takeover rules and how much is a function of market and credit conditions is a subject that merits more rigorous research.

Perhaps a more important question to ask in light of the previous conclusions on overseas deals in the UK is this: “What measures are in the best long-term interests of the UK capital markets?” A tightening of calendar and reporting restrictions by The Panel on the one hand, or a liberalisation of the takeover rules on the other? The fundamental responsibility of The Takeover Panel is to ensure that the shareholders of the offeree company are supported and are not deprived of their long-term value rights by short-term speculators playing the private to public market arbitrage opportunities or, indeed, taking advantage of short-term valuation anomalies in share prices.

Volumes of academic research has pointed towards the long-term destruction of value from a substantial percentage of mergers and acquisitions activity, so perhaps the best outcome for all shareholders in the long-term is tough, aggressive anti-transaction action measures? The post-Cadbury rule changes are, therefore, another step on the way to ensuring a tougher climate for deal activity in the UK, a boon to UK PLC’s long term shareholders.

Paul Bisping is an Associate Lecturer at the London School of Business & Finance (LSBF).

This article has also been published by Business Sale Report.

Other Opinions and Features

The Rise of Mobile Accounting

Accounting has always been a field that’s associated with piles of paperwork, spreadsheet and staggering numbers. Using computers to carry…

What will the role of the CFO look like in the future?

The CFO role is often thought of as being largely preoccupied with numbers and data, but in the last few…

7 Myths About Accountancy

Wondering what accountancy is really like as a career? Many people think that being an accountant is just number crunching…